|

|

|

Col. Mitchell

Paige, Medal of Honor Recipient, Dies at 85.

|

| By Adam Bernstein Washington Post Staff Writer Tuesday, November 18, 2003; Page B06 Mitchell Paige, 85, a retired Marine Corps colonel who received the Medal of Honor after almost single-handedly staving off enemy forces during a crucial battle of World War II, died Nov. 15 at his home in La Quinta, Calif., southeast of Palm Springs. He had congestive heart failure. On Oct. 26, 1942, Col. Paige, who was then a sergeant, was leading a platoon defending a small but strategic airfield on jungle-covered Guadalcanal, part of the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. The islands and the airstrip, Henderson Field, were key positions in the defense of Australia. Col. Paige and his 33 men placed their few machine guns on a hilltop ridge, bracing for the inevitable: thousands of Japanese soldiers planning to rush them at night. To hear any sneak attack, Col. Paige placed C ration tins filled with empty bullet casings about 20 yards away, near the tall grass. It was, in fact, a noisy assault. He said the Japanese yelled in the darkness "Banzai!" and "Blood for the emperor!" One of his own men started a chorus of "Blood for Eleanor!" referring to first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Because of the sheer volume of Japanese troops he faced, Col. Paige ordered members of his platoon to fire until they or the enemy were dead or wounded. Soon, he was the only able-bodied American left on the ridge and solely held the Japanese at bay. In the pre-dawn, he darted from one machine gun to another, firing constantly to make the Japanese think he had a fully manned defense. He was under ceaseless threat. At one point, he said, he felt the heat from bullets that whizzed past his neck. His metal helmet also was struck by gunfire. As the battle waged into morning, he knew the enemy would see he was the only one standing. By then, U.S. reinforcements had arrived with bayonets. Col. Paige grabbed one of his machine guns, still burning hot after hours of use and charged into enemy lines with the others. The Japanese began their retreat. Besides the Medal of Honor, the military's highest award for valor, Col. Paige's decorations included the Purple Heart. He spent two more years in the South Pacific before returning home. He was a veteran of the Korean War and retired in 1964 as a full colonel. During the Vietnam War, he did advisory work to test high-powered rockets. Col. Paige, the son of Serbian immigrants, was born in the southwestern Pennsylvania town of Charleroi. On his 18th birthday, in 1936, he walked and hitchhiked to the nearest Marine Corps recruiting station -- in Baltimore, 200 miles away. After retiring, he spent years on a crusade to identify those who bought, stole and sold the Medal of Honor for profit or false glory. Starting in the mid-1990s, he worked in tandem with the FBI. "I couldn't arrest these guys before I got together with the FBI," he told Newsday in April, "but I scared the hell out of them and even got some of the medals back." Working with Rep. Al McCandless (R-Calif.), Col. Paige successfully lobbied for a provision in a 1994 crime bill that increased the penalties for selling a Medal of Honor from six months in jail and a $250 fine to one year in jail and a $100,000 fine. A friend in the FBI also helped Col. Paige on another issue of great personal interest: becoming an Eagle Scout. His old paperwork had never been properly submitted before he enlisted in the Marine Corps. In March, he received his Eagle Scout badge. "My heart is overwhelmed with joy," he said at the time. His first wife, Genevieve Paige, died in 1979. Survivors include his wife of 23 years, Marilyn Paige of La Quinta; two children from his first marriage, Mitchell J. Paige of Goddard, Kan., and Janis Bruha of San Mateo, Calif.; four stepchildren, Wendy Allaire of Laguna Hills, Calif., Judith Terry of Biggs, Calif., William Wylde of Whittier, Calif., and Robert Corey Wylde of Fullerton, Calif.; fifteen grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren. © 2003 Courtesy of The Washington Post Company |

|

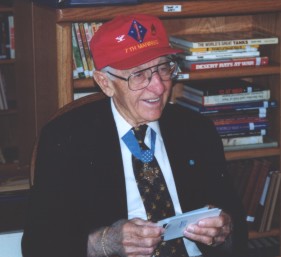

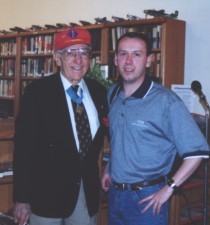

| It was the honor of a lifetime, to meet a Congressional

Medal of Honor recipient from World War II. In June of 2000, Retired

USMC Colonel Mitchell Paige visited Eldred and I joined the long line

of people who wished to meet him and maybe get an autograph and photo

taken with him. As seen above, I did manage to have a photograph of

us two together and Colonel Paige also signed my History of the United

States Marine Corps book. Colonel Paige was a great hero of the Pacific battlefield during World War II. He was one of thirty-five Pennsylvanians to receive the Medal of Honor during the war. Col. Paige took interest in my being a historian of military history and he even expressed a desire to visit my collection archive, but his schedule was always so tight that we never managed to break away for a few moments so he could tour my place. Each time Col. Paige returned to Eldred he always remembered me and was always the true "officer and a gentleman" to everyone around him. The United States Marine Corps and we have lost a hero, but he will never be forgotten. |

|

The President of the United States in the name of The Congress takes pleasure in presenting theMedal of Honor to MITCHELL PAIGE Rank and organization: Platoon Sergeant, U.S. Marine Corps. Place and date: Solomon Islands, 26 October 1942. Entered service at: Pennsylvania. Born: 31 August 1918, Charleroi, Pa. Citation: For extraordinary heroism and conspicuous gallantry in action above and beyond the call of duty while serving with a company of marines in combat against enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands on 26 October 1942. When the enemy broke through the line directly in front of his position, P/Sgt. Paige, commanding a machinegun section with fearless determination, continued to direct the fire of his gunners until all his men were either killed or wounded. Alone, against the deadly hail of Japanese shells, he fought with his gun and when it was destroyed, took over another, moving from gun to gun, never ceasing his withering fire against the advancing hordes until reinforcements finally arrived. Then, forming a new line, he dauntlessly and aggressively led a bayonet charge, driving the enemy back and preventing a breakthrough in our lines. His great personal valor and unyielding devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. |